PTSD: National Center for PTSD

Addressing Religious or Spiritual Dimensions of Trauma and PTSD

Addressing Religious or Spiritual Dimensions of Trauma and PTSD

Introduction

Traumatic experiences can involve life threat, loss, or moral dilemmas and thus may challenge people's spiritual or religious beliefs. However, mental health providers may feel unsure about how to address spirituality ethically and practically in their case conceptualization and treatment. This unease may be partially because scientists and health care practitioners are less likely to be religious than the general population, and partially because they often have little training in addressing spirituality despite the ethical mandate to consider cultural factors in working with their patients (1,2). This article will help mental health providers working with patients who have PTSD to incorporate research-based and clinical knowledge to assess spirituality and consider treatment options that acknowledge it. Clergy may also be interested in the included Resources Section.

Though in this article we will use both religion and spirituality to mean the search for the sacred, they can be defined somewhat separately. Religion often refers to the search for the sacred within the context of established faith-based institutions, whereas spirituality is the search for the sacred more broadly within a Higher Power or other divine or transcendent aspect of life (3). Definitions of these concepts vary, and unless specific to a research study that focuses on a particular construct, we use spirituality to refer to a person's overarching identity in their search for sacred, whether or not that includes a formal religion.

In This Article

Relationship of Trauma to Spirituality

Struggling to make spiritual sense of a trauma can cause significant distress because spirituality is one core aspect of cultural diversity that helps inform people's worldviews. Because of this, it may be helpful to directly address religion or spirituality within treatment for trauma. Indeed, there is some indication that often patients seeking mental health treatment are doing so as much for spiritual help as for mental health help (4) or that a subset of patients specifically want to include an open-ended discussion of spirituality in their treatment (5). There is also some indication that historically marginalized groups such as Black or Latino/a people are more often religious and wish for spirituality to be part of their health care (1,3). It is worth noting in the following discussion that the literature on spiritual strain following trauma is limited by the fact that much of the existing research is cross-sectional, includes mostly Christian faiths within the United States, and mostly focuses on a sub-set of traumas (especially combat, followed by natural disasters and sexual assault; 6).

Spirituality and post-trauma mental health may influence each other, in both positive and negative ways. This has less to do with people's dispositional spiritual identity and more to do with how they spiritually cope with adversity. Given that trauma often leads to a need to find meaning, and that spirituality often provides such a meaning system in people's lives, it follows that trauma can introduce a need to reconcile difficult events with beliefs.

Spirituality can be helpful when a positive relationship to one's own beliefs and practices buffer the effects of a trauma and provide a source of comfort during times of distress. This beneficial relationship, sometimes referred to as spiritual support or positive religious coping, has been found to be generally related to better functioning after trauma, including posttraumatic growth (6). This may happen because people increase their faith as it becomes even more meaningful to them, finding a great sense of purpose in life, closeness to a Higher Power, and sense of collaborating with a Higher Power to solve problems. For some people, an emphasis on forgiveness (of self or others) can be helpful (7), whereas for others, they may feel restored by the support they receive from prayer, from their faith community, or from their consistent relationship with a Higher Power (8). Some Veterans reported that their faith helped give them a sense of meaning or hope that their role in the military was a part of a larger fight for justness in the world (9).

On the other hand, for people who struggle to make sense of a trauma, their religious beliefs and doubts can lead to a decrease in religiosity and to greater distress that can in turn exacerbate PTSD (10). Spiritual strain, otherwise known as spiritual struggle or negative religious coping, has been consistently linked to poorer mental health after trauma (often more strongly than the link between positive religious coping and positive outcomes; 6, 11). Spiritual struggles may focus on a deity (e.g., concern about relationship to a Higher Power or concern that the devil is causing negative events), on interpersonal relationships (e.g., conflict with other church-goers), or on intrapersonal matters (e.g., feeling guilty about transgressions, having doubts about faith, or feeling a lack of meaning in life; 12).

In terms of trauma, some common spiritual struggles may involve:

Changed relationship to or conception of one's deity. That is, a traumatic event can cause people to experience changes in the way they see a Higher Power, such as feeling abandoned or punished by them, feeling angry at them, or questioning how a loving, all-powerful deity could allow horrible things to happen to the innocent. When religious meaning systems are very central, then individuals may either shift their pre-existing beliefs (e.g., "There is no Higher Power.") or their sense of the situation (e.g., "I must have done something wrong to provoke this punishment."). If people see an event as likely caused by punishment from a Higher Power or evil forces, they may have a sense of predictability while also feeling that the world is more cruel than previously thought. A changed relationship with one's faith can also be made more difficult if a trauma occurs during a stage of psychospiritual development in which there are already normative doubts and questions (e.g., early adulthood; 13).

Moral injury and guilt. For certain types of events, people may have committed or witnessed acts that go against their spiritual values, such as being involved in killing others. Exposure to potentially morally injurious events can lead to spiritual struggles and in turn to distress (14). There are times that different values are in conflict within a situation (e.g., patriotism and faith), creating uncertainty about the right course of action. Such experiences can lead to a sense of alienation from a Higher Power, feelings of failing one's faith, etc. When individuals experience trauma in childhood or early adulthood, they are often at a stage of psychospiritual development in which they believe that good people are always rewarded and bad people are always punished (13). The experience of trauma can then lead them to believe that they or others must be "bad" people. Similarly, for individuals who are at concrete stages of psychospiritual development, moral dilemmas introduce challenging ambiguity (13). For example, if one must shoot a child wearing a suicide vest to prevent 100 deaths, is that action right or wrong? To resolve these concerns, many clients benefit from interventions to help them see good/bad and right/wrong as continua rather than categories.

Difficulties with forgiveness. Within various faith communities, forgiveness is a central concept. After a trauma, there may be a push by others (or a perceived push) to forgive a perpetrator, leading to withdrawal from others if a person feels they cannot forgive in the way others want them to. Alternatively, a survivor may want to forgive others and feel unable to, thus feeling they have failed in how they want to live up to their faith's values. Finally, as with the moral injury above, people may have a difficult time forgiving themselves or their Higher Power, also leading to lingering distress (15). One study found that people who were more spiritual were more able to forgive themselves and others, which in turn was associated with better quality of life (7).

Finally, positive and negative religious coping are not necessarily mutually exclusive. It can be the case that wrestling with thorny spiritual questions can ultimately lead to a deepening or maturing of one's faith (9).

Clinical Considerations

Self-assessment

Providers may want to do a self-assessment of their own comfort with, knowledge of, and potential biases toward spirituality, given that training in this area can vary widely. Self-assessment could utilize the Religious/Spiritually Integrated Practice Assessment Scale or other self-report scales as helpful (16,17). Depending on patients' own background and desires for spirituality to be incorporated in treatment, providers may need more training or consultation to adequately address religious struggles or may feel that collaboration or referral would best suit patients' needs (3). Training can be helpful in thinking through potential ethical issues involved in providing spiritually conscious care (1). A self-assessment is also helpful to prepare for when patients ask about a provider's own spirituality. This question may be best answered by informing patients that it is the duty of mental health professionals to be spiritually informed in clinical practice, which often answers their question without disclosing personal information.

Assessment of patient's religion/spirituality

Similar to trauma itself, spirituality may not come up unless providers ask about it (see Hodge 2013 for an in-depth discussion of assessing spirituality and mental health; 18). So, it can be helpful to ask some questions in an initial intake or when assessing for the effects of trauma. Better understanding a patient's worldview helps providers to offer culturally informed care that fits their patients' needs.

For patients with a strong spiritual identity, providers can assess how their spirituality looks currently, and how trauma and spirituality affected each other. If spirituality is not a source of identity or conflict, the assessment may be quite brief. On the other hand, there are times that people experience a struggle with spirituality after trauma and find disconnecting from their faith to be the only way to move forward. In such cases, addressing spiritual distress may help them reconnect to this lost resource.

Questions such as the following may help to assess a patient's spirituality (19):

- Do you see yourself as a religious or spiritual person? If so, in what way?

- Are you affiliated with a religious or spiritual community?

- Were you raised in any particular faith or spiritual ideology? Do you still identify with that group, or any other group? Are there other groups that have an important influence on your spirituality?

- What are your ultimate values? What do you think your life is about, or what your ultimate goals are? What kinds of life goals are you most excited about?

- Has the traumatic event affected your religiousness [or spirituality] and if so, in what ways?

- Has your religion or spirituality been involved in the way you have coped with this event? If so, how?

- Do you have an interest in your mental health care incorporating a focus on your religion or spirituality? If so, how?

Gathering the above information—especially directly asking about patients' preferences for incorporating spirituality or religion into treatment—will help providers to conceptualize whether and how spirituality is affecting and was affected by trauma. It is important to note that pre-existing mental health concerns may also manifest as spiritual struggles in certain cases (e.g., people who are depressed may feel abandoned by their Higher Power as a function of their depression). It is important to consider when a spiritual belief may be driven more by mental health than by a spiritual belief system.

Certain measures may be helpful to supplement a clinical interview (20). Rather than general measures of spiritual orientation, it may be more fruitful to assess spiritual coping and struggles. For instance, the Brief RCOPE is a 14-item measure of religious coping with stressors, consisting of a positive and a negative coping scale. It has been used extensively in connection with mental health (21). The Religious and Spiritual Struggles Scale (and its brief version) is more recent but is also well-suited to assessing patients' struggles with spirituality (12,22). Although both are primarily designed for research purposes, they are likely to be useful clinically, both in opening conversations and in assessing change over time. They are, however, both Judeo-Christian; there is a lack of instruments that assess such constructs across other faith traditions.

Considerations for Collaboration and/or Referral to Clergy

When spiritual concerns are primary, it may be helpful to collaborate, consult or refer to clergy or to chaplains. Clergy refers to a larger group encompassing most religious leaders and includes chaplains. Chaplains are more specifically trained to provide counseling than most community clergy. Among hospital chaplains, there is specific training in working with medical teams, including mental health teams. Chaplains may be further trained in Clinical Pastoral Education to provide counseling. Chaplains are an important resource for mental health professionals who have little understanding of a patient's faith, or who have a faith that is different than a patient's. Even sharing a religious tradition with a patient does not mean a mental health professional will understand a patient's particular experience of that religion. Shared personal faith does not constitute training. Including clergy or chaplains can minimize the ethical risks of 1) engaging in a multiple relationship (i.e., acting as both clergy and therapist) and 2) practicing outside the bounds of one's own competence (1).

The purpose of any such consultation or involvement can be to help the patient assess, from within their own belief system, whether they are accurately interpreting the faith's beliefs as they apply to this event. For instance, if a patient is interpreting a near-death experience as a sense that a deity meant for them to die, this may be most appropriately challenged with someone who fully understands whether their belief system is consistent with this belief. In particular, chaplains have training in comparative religion, which can be helpful in identifying accurate or inaccurate sources of information.

Table 1. Considerations and Suggestions for Collaborating With Clergy

| Scenario | Potential solution |

|---|---|

| Patient brings in spiritual concerns | Start by asking the patient if they think clergy involvement would be helpful and open a conversation to learn how to best do so |

| Patient has a trusting relationship with a clergy person | Get a release of information for you to collaborate with clergy if patient is willing |

| Patient does not have a relationship with clergy or does not want to address a particular issue (e.g., addiction) with their known clergy | Consider connecting patient with a chaplain (available at VA's or other hospitals) |

| Patient does not want to work with a clergy person or chaplain | Consider connecting patient with a spiritual director or companion (these are people who can provide spiritual reflection and guidance but are not affiliated with a particular church, denomination, or organization) |

| Patient does not want to work with a religious or spiritual professional | Do an anonymous consult with a clergy member or chaplain to help you better understand the tenets of your patient's religion |

Considerations for PTSD Treatment Related to Spirituality

Spiritual integration continuum

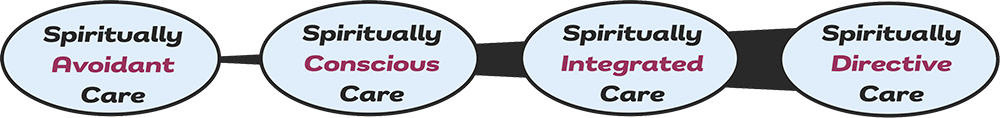

Some have conceptualized spiritual integration into therapy to vary on a continuum from spiritually avoidant care through spiritually conscious, spiritually integrated, to spiritually directive care (23,24).

- Spiritually avoidant care, in which providers neither assess for nor address religion/spirituality, is likely to be less helpful when spirituality is important to a patient or is a source of mental or emotional strain.

- Spiritually conscious care is an approach in which the provider assesses for spirituality and religion and remains open to their potential importance throughout treatment (24) and should likely be the minimum level of care for any mental health provider.

- Spiritually integrated care tailors treatment to help meet a patient's own goals for spiritual meaning.

- Spiritually directive care focuses directly on spiritual beliefs and might use spiritual practices such as prayer as a modality within treatment.

Whether to practice spiritually integrated or spiritually directive care will depend on patient desire—for spiritually integrated or directive care, explicit informed consent should be assessed both early and later (1). Level of integration will also depend on provider training, competence and availability. Ideally, any provider would be capable of providing spiritually conscious care (potentially with consultation as needed), but spiritually integrated or directive care will require more intensive and specific training that may vary depending on the specific treatment or practice.

The following options can be considered, ranging from a more minor to a more major focus on spirituality in treatment, whether with you, another provider, or in collaboration with clergy.

Address spiritual concerns as they arise in PTSD treatment

In a spiritually conscious care approach, providers assess for spirituality at the start of treatment and then listen for spiritual concerns throughout treatment. For providers offering first-line PTSD treatments, this may mean listening for ways that behavioral avoidance or cognitive distortions relate to spiritual concerns, for instance. When spiritual concerns or struggles are identified, providers can look for ways in which they may have been affected by the experience of trauma and resulting mental health symptoms. For instance, if a loss of faith was precipitated by the experience of a trauma, how was the patient interpreting what happened and why? How does that fit into their religious belief structure, and how has trauma challenged that belief structure?

When spiritual concerns are raised in therapy sessions, it is important that mental health professionals respond in a way that is consistent with their area of psychological expertise and training. For instance, imagine a patient who is very religious and is sexually assaulted, then coming to believe that their Higher Power must have meant for them to be assaulted. If this patient is in Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT), the provider can use the tools of the therapy to help them challenge that thought. However, the provider must have a clear understanding of what the patient's particular faith believes about predestination and the nature of their Higher Power before doing so. In many cases it may also be helpful to consult with a clergy member to ensure accuracy. Once the provider has an understanding, they may help the patient think about questions such as whether this is something they always believed (vs. a fluctuating mood-based belief), where the belief started, and whether others within their faith (including clergy) believe the same thing. All the above can be within mental health providers' scope but challenging a religious belief without first having an understanding of their religion risks deep misunderstanding and invalidation of patients' beliefs.

Likewise, there may be many ways within Prolonged Exposure (PE) to also incorporate a focus on religion when helpful for a patient (8). In vivo exercises might involve attending a religious service. Cognitive distortions related to the trauma and faith may be explored in the processing of imaginal exposure (using some of the same principles outlined above).

Consider a treatment that implicitly or explicitly addresses spirituality

Certain treatments that have been tested for PTSD, moral injury, or trauma-related guilt incorporate some amount of spiritual focus. Each of these treatments has preliminary evidence for their efficacy with a PTSD population, though not as much as first-line treatments for PTSD (i.e., none of the following are recommended in the VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline).

For instance, Adaptive Disclosure-Enhanced (25), Impact of Killing in War (26), and Trauma-informed Guilt Reduction Therapy (TrIGR; 27) were not developed to explicitly incorporate religion. However, given that they specifically address personal values and meaning making in the wake of trauma and potentially morally injurious events, they may allow more naturally for a discussion of spirituality to be included in treatment. Thus, they may help provide frameworks for addressing spiritual struggles.

Others, such as compassion-based meditation (e.g., CBCT-Vet;28) or Loving-kindness Meditation (29), are based in Eastern religious traditions—though often practiced secularly—and involve an explicit focus on forgiveness, compassion and acceptance in ways that may be helpful for patients wanting to increase healthy spiritual functioning.

Mantram Repetition Program (MRP; 30-32) is more explicitly spiritual. In this mantram-based group intervention for the treatment of PTSD, patients select a 'mantram,' which is a sacred (often religious) word or short phrase that is repeated frequently to raise awareness and redirect thinking and behavior throughout the day. Mantram repetition is paired with additional tools of slowing down and one-pointed attention to support attention training and emotion regulation. Patients do not have to have any spiritual beliefs to engage in the intervention. The treatment can be delivered by mental health professionals with training in MRP.

Finally, Building Spiritual Strength (BSS; 33,34) is a trauma-focused group treatment designed to specifically address spiritual concerns and build on areas of healthy spiritual functioning to contribute to positive adjustment. Spiritual concerns caused by conflicting moral principles are resolved using cognitive strategies to develop alternative perspectives and recognize the complexity of multiple moral codes. The treatment is inclusive of all faith and non-faith belief systems and can be delivered by chaplains and mental health professionals with training in spiritually integrated counseling and specifically in this intervention.

Summary

Religious and spiritual beliefs can be tested and strained by traumatic experiences and by PTSD symptoms. Mental health providers can help by assessing for such strains and for patient's preferences for addressing them in treatment, then choosing ways to integrate a focus on religion or spirituality within PTSD treatment.

Resources

- Clergy Toolkit, designed to help clergy members who work with Veterans and others who have PTSD

- VA's Whole Health approach to Spirit and Soul, addresses forgiveness, coping, and spiritual practice

- PTSD Consultation Program, available to any provider who works with Veterans who have PTSD, offers guidance on any relevant questions and maintains a recorded webinar (Adobe Connect) by Dr. J. Irene Harris from 2019: Spirituality and PTSD

References

- Currier, J. M., Fox, J., Vieten, C., Pearce, M., & Oxhandler, H. K. (2023). Enhancing competencies for the ethical integration of religion and spirituality in psychological services. Psychological Services, 20(1), 40-50. https://doi.org/10.1037/ser0000678

- Shafranske, E. P., & Cummings, J. P. (2013). Religious and spiritual beliefs, affiliations, and practices of psychologists. In K. I. Pargament, A. Mahoney, & E. P. Shafranske (Eds.), APA handbook of psychology, religion, and spirituality (Vol 2): An applied psychology of religion and spirituality (pp. 23-41). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/14046-002

- Park, C. L., Currier, J. M., Harris, J. I., & Slattery, J. M. (2017). Trauma, meaning, and spirituality: Translating research into clinical practice. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/15961-000

- Fontana, A., & Rosenheck, R. (2004). Trauma, change in strength of religious faith, and mental health service use among Veterans treated for PTSD. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 192(9), 579-584. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.nmd.0000138224.17375.55

- Currier, J. M., Pearce, M., Carroll, T. D., & Koenig, H. G. (2018). Military Veterans' preferences for incorporating spirituality in psychotherapy or counseling. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 49(1), 39-47. https://doi.org/10.1037/pro0000178

- Kucharska, J. (2020). Religiosity and the psychological outcomes of trauma: A systematic review of quantitative studies. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 76(1), 40-58. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22867

- Currier, J. M., Drescher, K. D., Holland, J. M., Lisman, R., & Foy, D. W. (2016). Spirituality, forgiveness, and quality of life: Testing a mediational model with military Veterans with PTSD. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 26(2), 167-179. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508619.2015.1019793

- Currier, J. M., Holland, J. M., & Drescher, K. D. (2015). Spirituality factors in the prediction of outcomes of PTSD treatment for U. S. military Veterans. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28(1), 57-64. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.21978

- Foy, D. W., Drescher, K. D., & Smith, M. W. (2013). Addressing religion and spirituality in military settings and Veterans' services. In Aten, J., O'Grady, K., & Worthington Jr, E. (Eds.), The psychology of religion and spirituality for clinicians: Using research in your practice (Vol. 2): An applied psychology of religion and spirituality (pp. 561-576). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/14046-029

- ter Kuile, H., & Ehring, T. (2014). Predictors of changes in religiosity after trauma: Trauma, religiosity, and posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 6(4), 353-360. https://doi.org/10.1037/a00344880

- Smith-MacDonald, L., Norris, J. M., Raffin-Bouchal, S., & Sinclair, S. (2017). Spirituality and mental well-being in combat Veterans: A systematic review. Military Medicine, 182(11-12), e1920-e1940. https://doi.org/10.7205/MILMED-D-17-00099

- Exline, J. J., Pargament, K. I., Grubbs, J. B., & Yali, A. M. (2014). The Religious and Spiritual Struggles Scale: Development and initial validation. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 6(3), 208-222. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036465

- Harris, J. I., Park, C. L., Currier, J. M., Usset, T. J., & Voecks, C. D. (2015). Moral injury and psycho-spiritual development: Considering the developmental context. Spirituality in Clinical Practice, 2(4), 256-266. https://doi.org/10.1037/scp0000045

- Evans, W. R., Stanley, M. A., Barrera, T. L., Exline, J. J., Pargament, K. I., & Teng, E. J. (2018). Morally injurious events and psychological distress among Veterans: Examining the mediating role of religious and spiritual struggles. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 10(3), 360-367. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000347

- Currier, J. M., Drescher, K. D., & Harris, J. I. (2014). Spiritual functioning among Veterans seeking residential treatment for PTSD: A matched control group study. Spirituality in Clinical Practice, 1(1), 3-15. https://doi.org/10.1037/scp0000004

- Oxhandler, H. K., & Parrish, D. E. (2016). The development and validation of the religious/spiritually integrated practice assessment scale. Research on Social Work Practice, 26(3), 295-307. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731514550207

- Oxhandler, H. K., & Pargament, K. I. (2018). Measuring religious and spiritual competence across helping professions: Previous efforts and future directions. Spirituality in Clinical Practice, 5(2), 120-132. https://doi.org/10.1037/scp0000149

- Hodge, D. R. (2013). Assessing spirituality and religion in the context of counseling and psychotherapy. In K. I. Pargament, A. Mahoney, & E. P. Shafranske (Eds.), APA handbook of psychology, religion, and spirituality (Vol. 2): An applied psychology of religion and spirituality (pp. 93-123). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/14046-005

- Harris, J. I. (2019, February 20). Spirituality and PTSD [Webinar]. National Center for PTSD. https://va-eerc-ees.adobeconnect.com/p7rn4t91qdz/

- Hill, P. C., & Edwards, E. (2013). Measurement in the psychology of religiousness and spirituality: Existing measures and new frontiers. In K. I. Pargament, J. J. Exline, & J. W. Jones (Eds.), APA handbook of psychology, religion, and spirituality (Vol. 1): Context, theory, and research (pp. 51-77). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10 .1037/14045-003

- Pargament, K., Feuille, M., & Burdzy, D. (2011). The Brief RCOPE: Current psychometric status of a short measure of religious coping. Religions, 2(1), 51-76. https://10.3390/rel2010051

- Exline, J. J., Pargament, K. I., Wilt, J. A., Grubbs, J. B., & Yali, A. M. (2022). The RSS-14: Development and preliminary validation of a 14-item form of the Religious and Spiritual Struggles Scale. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/rel0000472

- Saunders 2010

- Harris, J. I., Chamberlin, E. S., Engdahl, B., Ayre, A., Usset, T., & Mendez, D. (2021). Spiritually integrated interventions for PTSD and moral injury: A review. Current Treatment Options in Psychiatry, 8(4), 196-212.

- Darnell, B. C., Vannini, M. B. N., Grunthal, B., Benfer, M., & Litz, B. T. (2022). Adaptive Disclosure: Theoretical foundations, evidence and future directions. Current Treatment Opinions in Psychiatry, 9, 85-100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40501-022-00264-4

- Burkman, K., Gloria, R., Mehlman, H., & Maguen, S. (2022). Treatment for moral injury: Impact of Killing in War. Current Treatment Opinions in Psychiatry, 9, 101-114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40501-022-00262-6

- Norman, S. (2022). Trauma-Informed Guilt Reduction Therapy: Overview of the treatment and research. Current Treatment Opinions in Psychiatry, 9, 115-125. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40501-022-00261-7

- Lang, A. J., Casmar, P., Hurst, S., Harrison, T., Golshan, S., Good, R., Essex, M., & Negi, L. (2017). Compassion meditation for Veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD): A nonrandomized study. Mindfulness, 11, 63-74. https:/doi.org/10.1007/s12671-017-0866-z

- Kearney, D. J., Malte, C. A., McManus, C., Martinez, M. E., Felleman, B., & Simpson, T. L. (2013). Loving-kindness meditation for posttraumatic stress disorder: A pilot study. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 26(4), 426-434. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.21832

- Bormann, J. E., Hurst, S., & Kelly, A. (2013). Responses to Mantram Repetition Program from Veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: A qualitative analysis. Journal of Rehabilitation Research & Development, 50(6), 769-784. https://doi.org/10.1682/JRRD.2012.06.0118

- Bormann, J. E., Thorp, S. R., Wetherell, J. L., Golshan, S., & Lang, A. J. (2013). Meditation-based mantram intervention for Veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: A randomized trial. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 5(3), 259-267. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027522

- Bormann, J. E., Thorp, S. R., Smith, E., Glickman, M., Beck, D., Plumb, D., Zhao, S., Ackland, P. E., Rodgers, C. S., Heppner, P., Herz, L. R., & Elwy, A. R. (2018). Individual treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder using mantram repetition: A randomized clinical trial. American Journal of Psychiatry, 175(10), 979-988. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17060611

- Harris, J. I., Erbes, C. R., Ejgdahl, B. E., Thuras, P., Murray-Swank, N., Grace, D., Ogden, H., Olson, R. H. A., Winskowski, A. M., Bacon, R., Malec, C., Camion, K., & Le, T. (2011). The effectiveness of a trauma-focused spirituality integrated intervention for Veterans exposed to trauma. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 67(4), 425-438. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20777

- Harris, J. I., Usset, T., Voecks, C., Thuras, P., Currier, J., & Erbes, C. (2018). Spiritually integrated care for PTSD: A randomized controlled trial of "Building Spiritual Strength." Psychiatry Research, 267, 420-428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.06.045

You May Also Be Interested In

VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for PTSD (2023)

Get information on evidence-based treatment recommendations for PTSD.

Clinician's Guide to Medications for PTSD

Get key information and guidance on the best medications for PTSD.